How To Cross Genres

The various Star Wars films take place across many different planets. They prominently feature spaceships and space travel. There are futuristic weapons, like laser blasters and lightsabers. Despite this, Star Wars doesn’t really feel like science fiction in the same way that Alien or Star Trek does.

I would argue that Star Wars is not “true” science fiction, because science and technology are not central to the story. Star Wars is concerned with destiny and “the Force” – in other words, magic. The setting of Star Wars has the trappings of technology that is beyond our current capabilities, such as faster-than-light interstellar travel. However, you could remove any of the specific technology of Star Wars (such as replacing the lightsabers with swords or the different planets with different kingdoms) and the story would be the same. Star Wars has more in common with fantasy, fairy tales, and mythology than “classic” science fiction.

This has nothing to do with the fact that Star Wars is set “[a] long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.” Science fiction does not need to take place in the future or involve earthlings, although it usually does. However, it must grapple with issues raised by science or technology – the mythology of Star Wars is universal enough to take place in any setting.

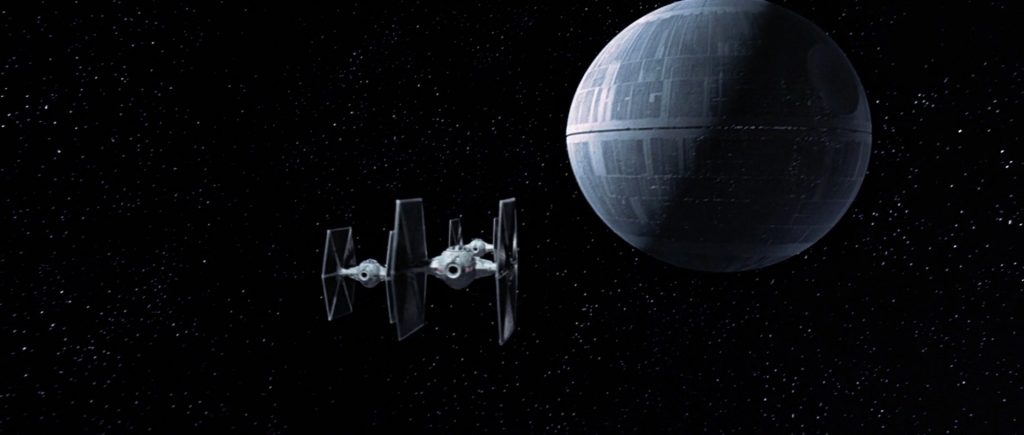

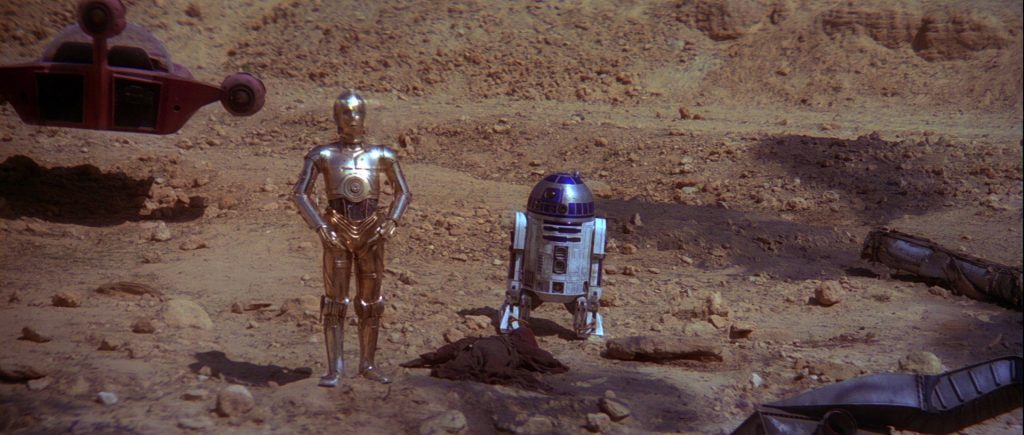

Of course, there are science fiction elements in the Star Wars films. The plot of the original film, for example, involves the empire developing new weapons technology. The imposing symmetry of the imperial ships contrast sharply with the overgrown chaos of Yoda’s training grounds, which hints at a tension between nature and science. There are also interesting moral questions raised by the way droids are treated in the films, although this wasn’t explored in-depth until the recent Han Solo origin film.

How To Reveal an Environment

One very basic principle of setting a scene is to either start on a wide shot and gradually cut closer or to start on a close up shot and work your way out. Going from wide to close gives a lot of information to the audience and helps to establish the geography of the scene.

Going from close to wide creates a sense of mystery for the audience; by beginning with unexplained detail shots, you create a sense of anticipation, and the later wide shots become a reveal.

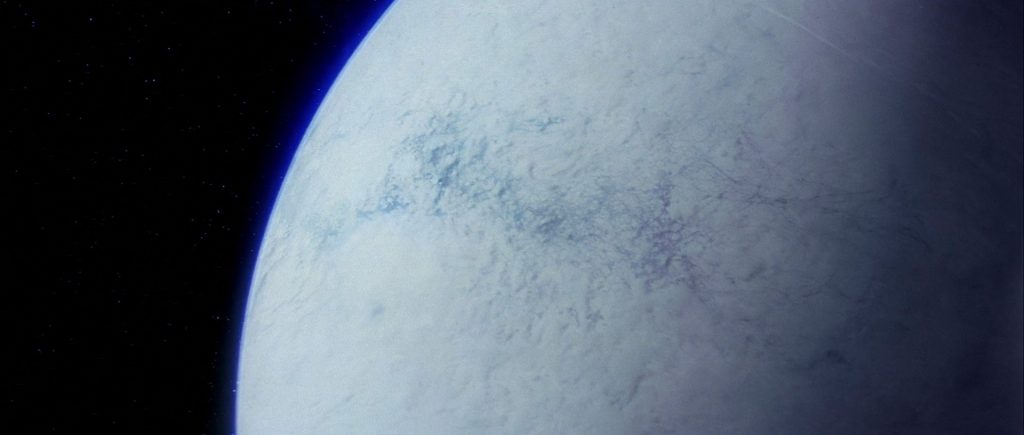

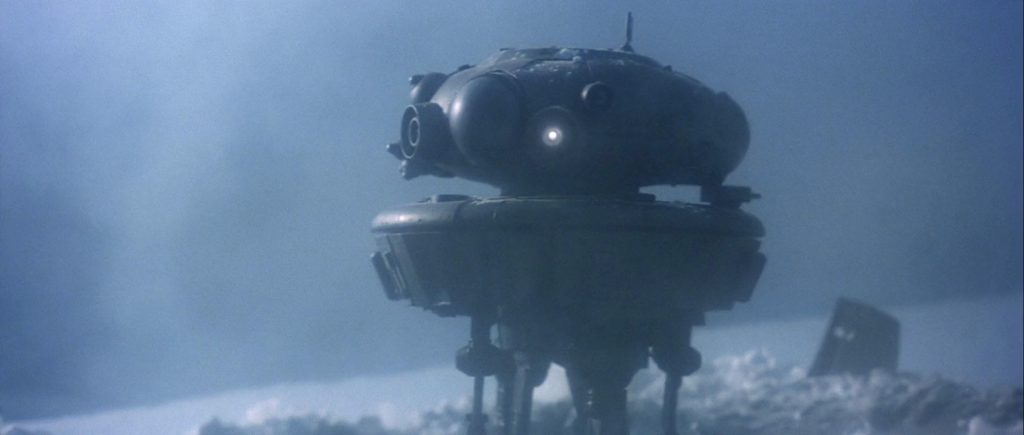

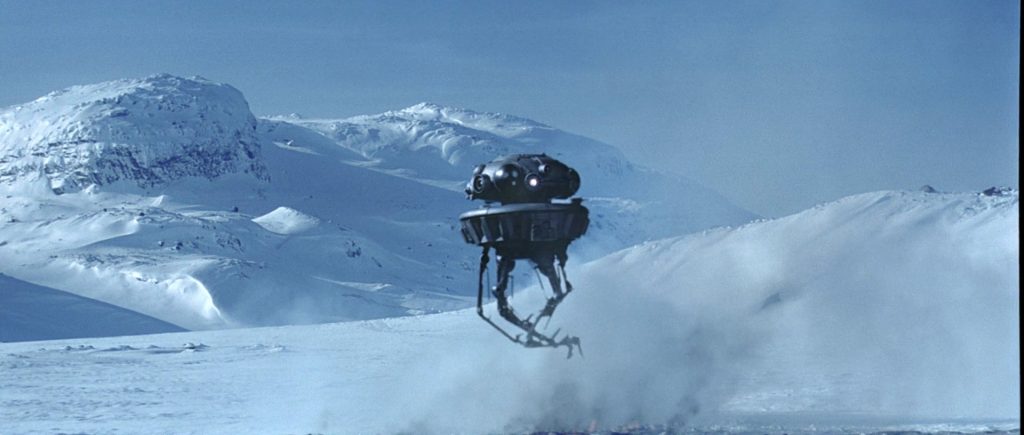

In the opening sequence of The Empire Strikes Back, we first go from wide to close, beginning with a shot from the planet from space, then a wide aerial shot of the probe entering the atmosphere, then to a slightly closer shot of the ground as the probe hits. The next shot is a close up of the probe, which makes the following wider shot of the probe an interesting reveal for the audience.

This technique of going from wide to close and close to wide is a great way to give the audience information about the environment of a scene and to hold their interest by gradually providing new details.

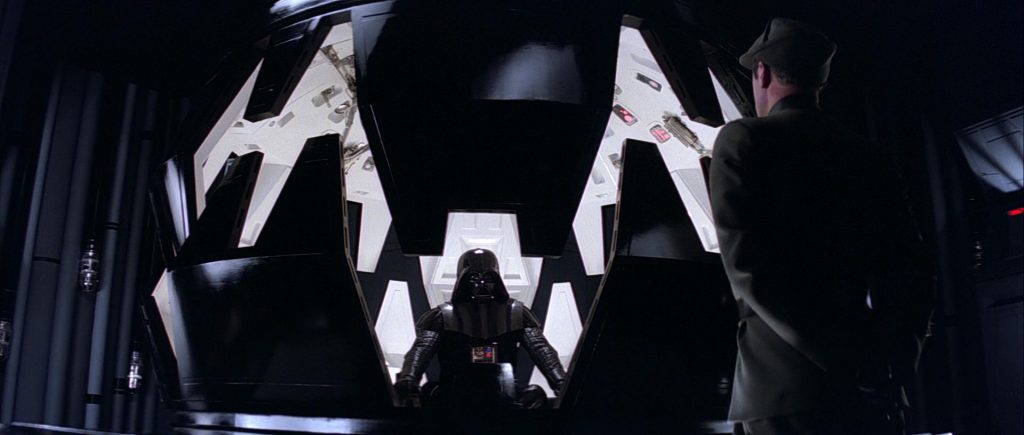

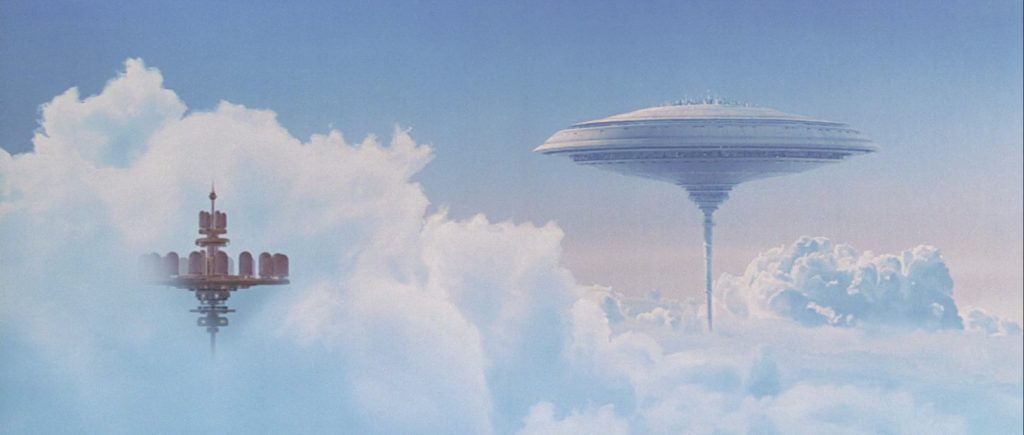

This sequence from later in the film also begins extremely wide and gradually moves closer. Eventually, the shot settles into a shot/reverse shot – note the adherence to the 180 degree rule.

How To Create Mystery

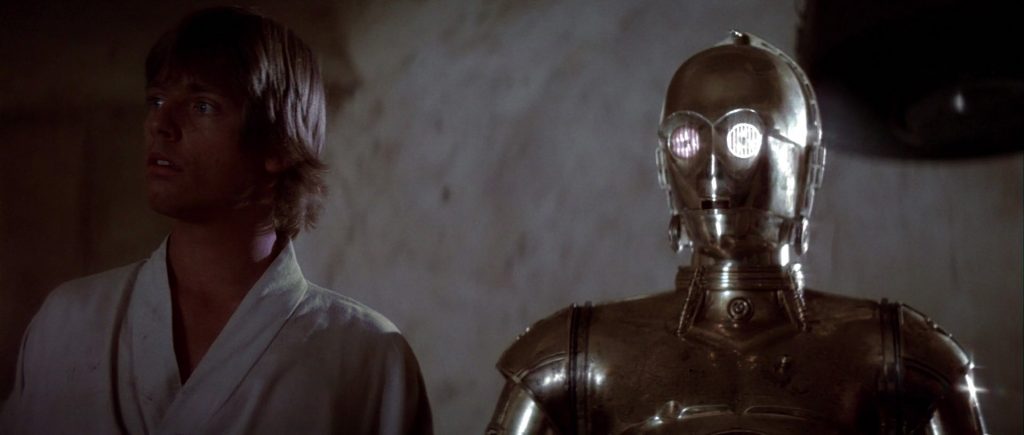

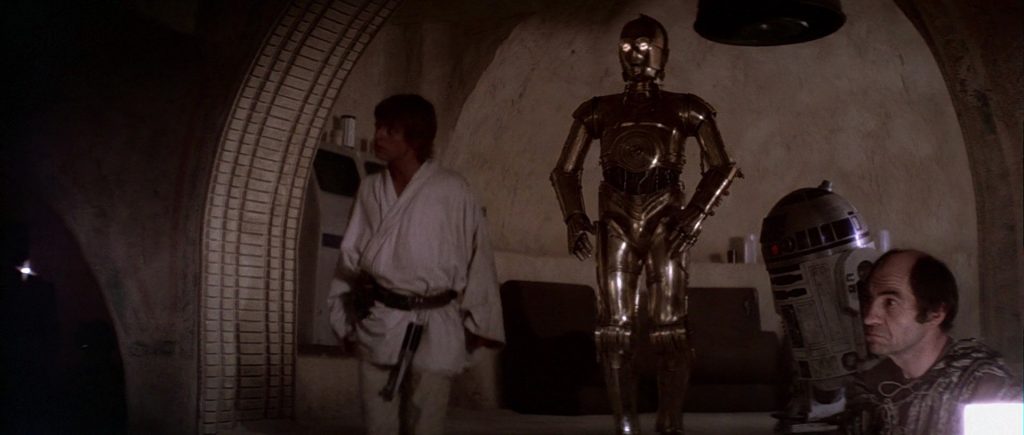

This technique is similar to the one described above. In the following sequence from Star Wars, the scene begins with a sequence of close detail shots from the environment; in this case, various aliens in a cantina. Here, we see four different shots of aliens before a medium close-up of Luke and C-3PO. Then we see the bar in a wide shot from their perspective. The camera movement (a pan) helps emphasize that this is a point-of-view shot.

The camera continues to alternate between shots of the bar’s exotic denizens and reaction shots of Luke and C-3PO, until we finally cut to a longer shot of them walking forward into the bar. At this point, there is an exchange between Luke and the bartender and the story advances.

Without any additional context, the close up shots of strange creatures at the beginning of the scene creates a sense of mystery, even confusion. When we eventually see Luke and C-3PO, we realize that we are experiencing this place through their perspective – and their reaction shots show that it is an unfamiliar environment for them as well.

As the sequence progresses, Luke has an altercation with another patron and Obi-Wan has to step in. Because the scene begins with shots of the aliens, it’s easy to believe that this is a strange, potentially dangerous place. If the sequence started with Luke already at the bar, the tense exchange that follows would not work nearly as well.

How to Tell a Story with Lighting

In The Empire Strikes Back, the main characters have adventures in several wildly different environments, including an ice planet, an asteroid field, a foggy swamp, and deep within an industrial mining facility. The production design does a lot to make these different locations feel distinct, but so does the lighting. As the sun sets on Hoth, the dim, blue lighting makes the shots feel cold; back in the bunker, the harsh uplighting makes the environment feel tense as the battle progresses.

On Dagobah, the cool, diffuse lighting outside contrasts with the warm, contrasty light in Yoda’s hut. In the mining facility on Bespin, some of the shots recall the tense, directional lighting in Alien. In the room where Han is frozen in carbonite, the orange foreground lighting and blue background lighting are a classic example of a complementary color scheme.

Despite its fantastical settings, The Empire Strikes Back always does a good job of “motivating” its lighting. Lighting is motivated when the audience can attribute its presence to something in the world of the film. For example, the warm lighting in Yoda’s hut is motivated, because we see shots of a fire in the room. In the shots below, the red and purple lights on Han’s face are motivated because we can see the devices that (we assume) are creating the lights.

Subtle lighting doesn’t need to be specifically motivated; we can assume that there is some light in any given environment. However, when lighting is used for a specific effect, it’s important to ground it in the world of the film.